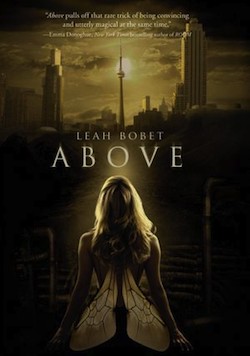

Leah Bobet’s first novel, Above, is a young adult urban fantasy—in the sense that “urban fantasy” means “fantasy set in a city”—published this week by Arthur A. Levine Books/Scholastic. The novel is told by Matthew, the first child born to a subterranean community called Safe—a place for Freaks, Beasts, and the Sick. His role in the community is as Teller: he remembers and recites the stories of the people. When the only member to ever be exiled comes back with an army of hungry shadows, driving him from his home and onto the unfriendly streets of Above, he and the few escapees must find a way to save their community; however, things are not as they seem, and the situation is not as clear-cut as Matthew once believed.

Spoilers follow.

Above is a book with sharp edges. Bobet casts a critical and incisive eye on her characters’ fears, failings, wants, needs—and what they are capable of, for better or worse. Above also deals intimately and wrenchingly with mental illness, the ways that we treat people who we deem Other in our society, the complexities of truth-telling, and what makes right or wrong. Issues of gender, race, abuse, and sexuality are also prevalent in this world of outcasts, both literally and metaphorically.

Above is a difficult and engaging first novel, with prose that’s precise and practiced. The role of telling stories in this book—a patchwork of personal narratives, a fictional memoir told to us by the protagonist, Matthew—places a great weight on the words chosen to do so. Bobet’s prose stands up to the task she sets before it: telling a complicated and fantastical story of a bloody, dangerous, heart-twisting coming of age where what there is left to be learned is “one dark true thing that you can’t save them And most times, child, you can’t save you, either.” (273)

However, seeing how involved it is with issues of mental illness and social brutality, the part that I most want to talk about in regards to Above is the ending. There are two reasons for this—the first is how Bobet resolves a plot thread that made me initially uncomfortable: the fact that Corner, the shadow-spinning villain whom the denizens of Safe are taught to fear, is an intersex person and is gendered by them as “it.” Considering that the entire text is about constructions of alienation and Othering, I suspected that Bobet was not going to leave the situation in such a problematic place, and to my relief she doesn’t. Corner—really named Angel—was not a villain, as we discover by the end; sie is in fact the most sympathetic, heart-breaking character in the novel, for the ways in which sie was betrayed and reviled by the people sie most trusted to love and keep hir safe.

Matthew’s realization that the people he loves and considers family have brutalized Corner so thoroughly is a high-point of the book:

“But that’s what sent Corner mad,” I say, ’cause if Corner’s not mad, with all that bleeding and fighting and wanting to die, I’m a I don’t know what I am. “It went mad because of the lying. All of us inside, keeping up this Tale of how it was Killer, and not letting it back home. We—” and I pause, feeling notebook pages under my fingers. “We said its real wasn’t real. We left it out to die.”

The finale of the book is Corner’s tale, told on the inside of Matthew’s head while sie dies, with the pronouns sie preferred. She tells the truth of hir childhood with a supportive, wonderful mother who wanted to let hir by hirself—and then that mother’s death, and the medical/psychiatric institution’s abuse of hir. There are no villains in this novel, only people who are driven too far and too hard past their limits, and who do what they must to survive and make right. While Corner is a tragic antagonist, I found that the plot of the novel—less about reclaiming Safe and more about finding the truth around what manner of evil was done to Corner to drive hir to do what sie did—and Bobet’s structuring of the final scenes ameliorate much of the potential ill of the stereotype of the intersex villain. I suppose that what I’m saying in this case is: your mileage may vary, but by the conclusion, I felt that Bobet had both examined and moved past the destructive trope that I initially feared.

This also ties in to the second issue I was concerned with, in a more nebulous way: the characterization of Ariel, a girl who transforms into a bee and a girl with an illness both. By the end of the text, Bobet makes it clear that the white/black divide between the denizens of Safe and the “Whitecoats” they fear is as potentially destructive as it is helpful; Doctor Marybeth, a First-Peoples woman who initially released Atticus and Corner from the asylum they had been admitted to, is a central figure. Mental illness is not cute and desirable here; neither is the psychiatric institution entirely evil, or particularly good. The second most devastating—but uplifting, in its way—scene in the book is the absolute finale, where Matthew asks Ariel to go Above and let Doctor Marybeth help her try to get well with the good sort of doctors, the ones who want to heal. As Matthew says, “ there wasn’t no shame in healing.”

His understanding that not only does he have no right to hold Ariel with him, down below in Safe, but that the doctors might be able to help her if they are “good” doctors like Marybeth, is a bloom of the positive and hopeful in an ending colored with funerals and too many bodies to burn. Above sticks its landing, so to speak. These are multifarious, fraught, visceral themes to deal with on their own, let alone all in one book, but Bobet weaves Matthew’s Tale for us in careful pieces, with compassion and understanding for every character in the text. That Corner gets to tell Matthew and us hir story in hir own words is valuable; that Matthew, who so often saw himself as Ariel’s protector, her knight in shining armor, is able to realize that his perception of her as helpless was wrong; that Ariel, hurt so often and afraid for herself and those she loves, makes the decision to try and heal—these are all key elements that settle Bobet’s story. The emotional desolation of the morally ambiguous murder of Corner and the later funerals is given a moment of brightness and possibility, because the survivors continue to survive. Whisper goes up Above to find her lifelong lover Violet again and take care of her. Matthew commemorates the lost and the damaged in a new door-carving, including Corner’s story most of all.

There are no easy answers in Above, and no simple decisions, and no path that is all goodness and light. There are necessary, impossible decisions, and there is guilt. There is real heart-break. Above is a bleak novel in the best way; it provokes and prods and forces the reader to acknowledge things that hurt to see. For that, and for its inclusion of queer folks, people of color, and disabled characters as fully human and fully real, I appreciated it a great deal.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic and occasional editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. Also, comics. She can be found on Twitter or her website.